We always spend the time and energy at the beginning of any initiative to ensure that we have the right objectives – putting together this program for The Value Web has pushed us to get specific about what makes a set of objectives “right” or not…especially when you’re trying to make far-reaching changes with your efforts.

There are the obvious table-stakes of “SMART” objectives – basically, are they well crafted and specific enough to be able to tell you’re achieving them. There’s the design-thinking approach of feasibility/viability/desirability – but in a systems-change context this only raises the main question; desirable for whom?

The fact is that systems change happens all the time – sometimes unintentionally, but often very much with intent, and in many cases the systems we may be trying to change are working exactly as someone else may have intended.

CV Harquail’s three questions to guide decision-making get closer to it: Who benefits? Who is left behind? Is this what we want?

These simple questions, for me, at least start to surface key issues in systems change – that benefits and impacts won’t be the same for everyone, and we must be conscious of the choices we make. It also connects well with my overall belief that we are exiting the age of externalities, where we can blithely write off the impacts of our actions as external to our value calculations.

So from my perspective, we can’t say what the “right” objectives are without having a declared point-of-view on the kind of systems change we are looking for.

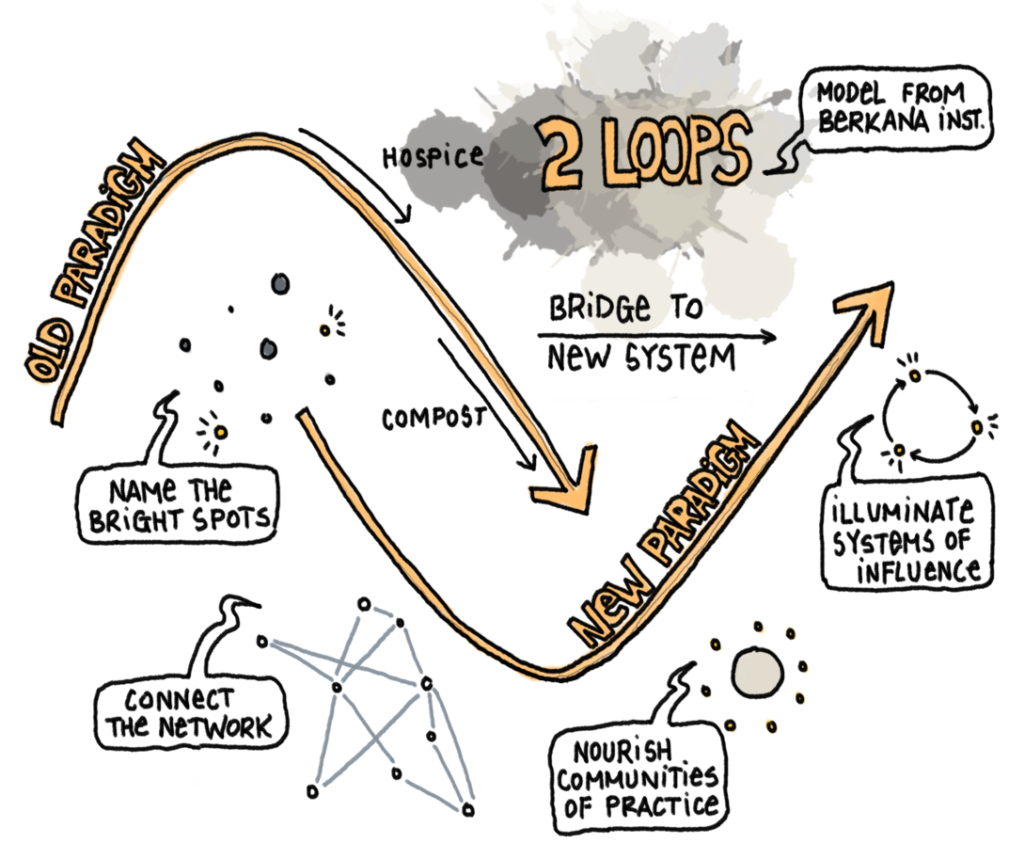

The Berkana Institute has its “Two Loops” model which describes the move from an old paradigm to a new one. I think this model is useful in thinking through the non-linear move from one ruling set of norms to a new one.

But setting intentional about designing the shift from one system, or one paradigm, to another asks of us what we plan to leave behind, what we want to bring into being, and why. It also begs the question of what right we, as individuals, have to make that change. I’ll address the “who” question separately. For now, I’ll focus on whether a set of objectives in driving systems change are “right” or not.

I offer these guidelines for whether a set of systems change objectives are the right ones. I would be suspicious at any kind of change effort that:

- Benefits an in-group at the expense of out-groups

- Leverages weakness or imbalance to propagate its effects

- is based on limited definitions

- Internalizes gain and externalizes harm

These are the kinds of “system change” that I think – using the Two Loops Model, represent the paradigm we should be leaving behind. Think through the accomplishment of your objectives to the fullest extent – what would result from achieving them? What would the second and third-order effects be?

Keep in mind John Sterman’s admonition: “There are no side-effects – there are only effects.”

The test for objectives that represent “healthy systems change”, then, would create change that:

- Is seen as improving the conditions for all parties involved

- Is supported by the contributions of parties across the system

- Is informed by networked knowledge from across the system

- Does not create harmful consequences beyond its own scope

I’m curious about the tests that others use to ensure their efforts will create truly “positive” change – what rules do you use to keep yourself on track?